The Expressive Noh Mask: A Moment's Movement Brims with Emotion

Noh, one of the world's most ancient performing arts, features actors donning masks, commonly known as Noh-men, as they take the stage.

Today, Mr. Oshima brought the actual masks he uses in his Noh performances.

In the Japanese language, the character for mask, 面 (men), is also read as omote and we Noh performers call them that. The principal actor, known as the shite (she-TAY), selects and wears these masks in accordance with their respective roles.

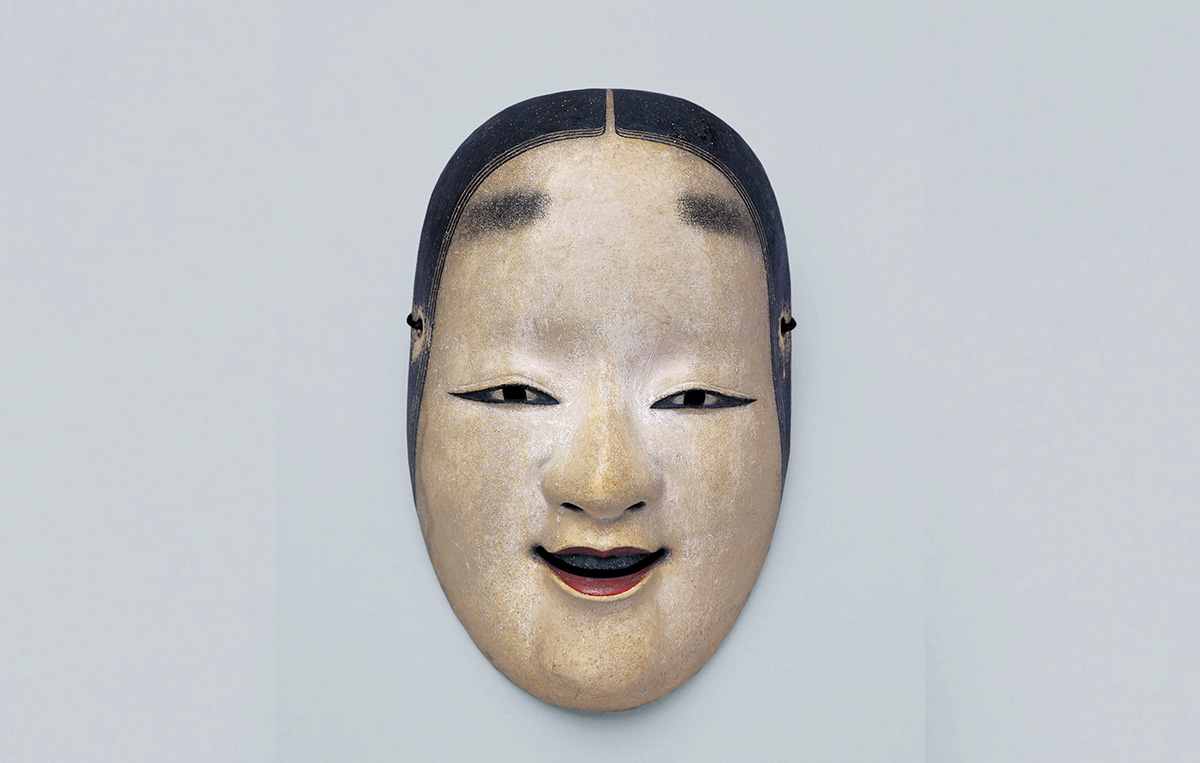

Among the fascinating array of Noh masks, there exists one called the ko-omote, designed specifically for portraying female characters aged between 15 and 19 years old. It's important to note that the shite embodies various entities, not limited to mere humans. They can personify gods, spirits, or even otherworldly creatures like demons.

These masks convey various emotions and expressions, despite their stoic appearance.

In Japan, the phrase 'a face like a Noh-mask' is used to describe someone who shows no emotions, a notion that Noh performers do not agree with. While they are carved from wood and may not change expressions realistically, they somehow appear to convey happiness or sadness, much like human emotions. Noh performers believe that these masks possess an intermediate expression that encapsulates all human emotions, which is why they use them to convey all kinds of feelings.

How are these emotional shifts achieved?

One could say that we evoke movement by not moving. During our performances, maintaining the fundamental angle of the mask and ensuring it doesn't shift is a critical skill. When emotions suddenly surge, tilting the mask ever so slightly downward brings forth a sense of sorrow hidden within the mask. Conversely, tilting it slightly upward accentuates a joyous expression. The subtlety of these changes demands intense concentration and energy from Noh performers. The fact that we hardly move means that when the angle of the mask does change, all emotions converge in that moment, which is the essence of Noh performance.

Noh Depicts Universal Themes of Human Emotions and Karma, Which is Why It Is Timeless.

What themes are commonly explored in Noh performances?

Noh primarily revolves around the joy of living and being alive, known as

Shūgen-Noh. In times when human existence was exceedingly arduous, expressing joy at simply being alive and giving thanks to gods and buddhas for one's presence in this world were significant themes in Noh. While Noh also delves into human sorrow, such as the regrets of those who perished in battle or the anguish of mothers separated from their children, and even feelings of resentment, these negative emotions are also part of the human experience.

Therefore, whether it's joy or sorrow, Noh encapsulates universal aspects of human life. These themes remain timeless, transcending centuries and epochs, making Noh perpetually relevant. Noh is also known for being a performing art that provides insight into the perspectives of the departed, offering glimpses into their observations of the present world. Mugen Noh (illusion Noh), a concept introduced by Zeami (1363-1443), focuses on the deceased as protagonists. In these performances, spirits of those who passed away decades or centuries ago appear before modern-day monks, allowing the audience to catch a glimpse of the otherworldly and hear about their lingering emotions through the main character shite.

Can we find expressions of shūgen (joy in being alive) in all Noh pieces?

For example, within the category known as Kyoujo Mono (madwoman plays), which involve a mother searching for a child she was separated from, there's a piece called Sumidagawa, considered one of the most tragic in Noh. While most Kyoujo Mono pieces end happily with the mother reuniting with her child, Sumidagawa is unique. In this piece, when the mother finally learns her child's fate, it's revealed that the child has already passed away. The scene ends with the mother reaching her child but unable to embrace them. Instead, all that remains is a field of overgrown spring grass, and the performance concludes as the morning sun rises.

Even amid such profound sadness, there's a sense of hope in the arrival of a new day and the affirmation of life. In this way, it serves as a kind of shūgen or celebration of life. While portraying the deeply sorrowful mother, the actor's role is to convey the mother's sadness to the audience. In Noh, actors use a simple hand movement known as shiori to express crying. Anything beyond this simple gesture would make it something other than Noh. Actors must be instruments through which the audience feels the sadness rather than personally experiencing it. This distilled approach to performance has been refined over the course of 600 years and continues to be the focus of Noh actors—to be instruments that amplify the audience's emotions.

Sharing Moments with Noh and Reveling in the Atmosphere Rather Than Seeking Meaning.

What significance do you believe Noh holds for us when we watch and experience it today?

It undoubtedly varies from person to person, but I believe that, ultimately, through the themes presented in Noh, the audience engages in a dialogue with itself. It's about introspection, reflecting on what elements of the sadness or beauty of a particular piece resonated with them and why. There's a saying that "Great Noh becomes interesting two days after watching it." Afterward, people often think, "What was that all about? Why did it affect me?" They recall their own sensibilities and past experiences, comparing them with the scenes and moments that left an impression. They engage in a dialogue with themselves, deepening their understanding. This process is highly fulfilling.

Being fulfilled and soothed by Noh is truly captivating, isn’t it?

In today's world, where simplicity is often praised, it's not to suggest that this approach is incorrect. However, easily comprehensible things can be rapidly consumed and forgotten. Taking a moment to pause and self-reflect, though it might seem burdensome, ensures that the experience isn't easily forgotten. It leaves a lasting memory in your heart as a lifelong treasure. About 80% of what makes Noh appear difficult is, in fact, the language used. Japanese people, in particular, may experience stress when they can't understand their own language. Excluding language, Noh is essentially quite simple. The script serves as clues to enter the piece. If you have a rough understanding of the overarching storyline, you don't need to obsess over the details. Instead, you can immerse yourself in the theme, feel the energy of the performance heading towards its climax, and savor the ambiance of the entire performance space with your senses.

What kind of theme are you preparing for the upcoming event at the Art Lobby on the Third Floor of the Main Tower?

For our October event, we aim to provide a welcoming and enjoyable experience for both Noh newcomers and enthusiasts. We plan to exhibit actual Noh masks and costumes, and to showcase stage photographs as well as a short performance of a scene from a Noh play. Visitors will have the opportunity to closely examine various masks, including the ko-omote I brought today. Noh masks, including the hannya mask, which evokes not only anger, but also the sorrow of a woman transformed into a demoness, reveal multifaceted emotions and showcase intricate techniques by the performers that visitors can appreciate up close. Furthermore, we will provide explanations in English to cater to our international guests.

In a hotel, which is an open space, it's a great pleasure to be able to intimately experience the beauty and power inherent in Noh. We hope to assist both domestic and international guests in experiencing the diverse charm of Noh, which resonates with the hearts of modern people, giving them a sense of ease as if they were dropping by casually.

Teruhisa Oshima's Profile

Teruhisa Oshima

Shite (the main protagonist), Kita School Noh actor.

Born in 1976 in Fukuyama, Hiroshima Prefecture. Designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Property.

Fifth-generation Oshima family member in the Kita School of Noh. Made his debut on stage at the age of 3 in the play Shōjō.

Performed major Noh plays such as Shōjōmidare, Dōjōji, Shakkyō, Okina, and Mochizuki.

Participated in numerous worldwide performances in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

In recent years, actively engaged in exploring new possibilities in Noh, including performances entirely in English called English Noh, sign language interpretations of Noh dialogues known as Sign Language Noh, and groundbreaking shows utilizing cutting-edge visual technology like VR Noh and 3D Noh. Also involved in planning and production.

▲ ko-omote (small mask)

ko-omote (small mask)

The ko-omote is a representative Noh mask used for female characters. With a slight movement of just 2-3 degrees, it can express a wide range of emotions, from joy to anger, and from sorrow to delight.

▲ Stage at a Noh theater

Stage at a Noh theater

The stage with a roof harkens back to the style of outdoor performances. The backdrop, known as the "mirror board," features evergreen pine trees, considered the dwelling place of deities, creating a stage setting where Noh is performed under the protection of gods and Buddhas. The bridge-like structure where characters appear is not just a passage: it symbolically connects the mortal world (this world) and the afterlife (the world beyond the curtain), imbuing it with profound significance.

Glossary of Noh Terms

| Shite (主役) | The protagonist. When portraying non-human entities such as ghosts or demons, the shite wears a Noh mask. |

|---|---|

| Waki (脇) | The supporting role, often portraying adult male characters from the mortal world, such as traveling monks, without wearing a Noh mask. |

| Kamae (構え) | A state of stillness. The fundamental movement of Noh often described as "moving sculptures." |

| Hakobi (運び) | Footwork or movement. |

| Noh-shōzoku (能装束) |

The costumes used in Noh. There are several rules based on colors and other factors depending on the role, and understanding these conventions can reveal information about the character's age, gender, status, and personality. |